Partner narratives

As part of the work we’re focusing on in the grant extension period (between now and September), we’ve been talking about the experience of traditional researchers partnering with patients. One thing we’ve identified is that these partners, like patients, also need resources, support, and encouragement as they do this work, especially as it is often not aligned with the traditional incentive structure for their work, either. One way of helping partners is by sharing stories and narratives from other partners who are doing similar types of work in partnership with patients. And of course, I also asked our team to write their own narratives to help draw out more insights from their experience on this Opening Pathways project. And I wasn’t disappointed - see below for the narratives and reflections from Erik, Eric, and John.

Erik Johnston’s partner narrative

Lessons from a humbled researcher

In the years leading up to my involvement in the opening pathways project I was developing a broad research and teaching agenda to help people and communities become more involved in their own fates. The goal still is to give them a sense of what is possible, connect them with resources (money, expertise, projects, time…), and support their journey. On May 18th, 2016, at the Quantified Self Conference in San Diego, I saw the most compelling talk of my academic career. A community of people with a shared challenge, themselves living with type-one diabetes or in someone they cared about, had the sense that they could create a closed loop artificial pancreas that would dramatically improve their lives. It was a compelling talk because it had a unique presentation, a collection of authentic voices, and especially because it was the clearest manifestation of how I hope to help many types of communities. It was not hypothetical, they improved their own lives and shared it with others. I will never forget the dad that said that because of the OpenAPS community, for the first time since his son was diagnosed, he could sleep through the night. That family’s quality of life was tangibly better.

For me, three light bulbs went off. This was a new kind of academic opportunity, to use the scientific process with the objective of being useful (more than publishable). Second, the talk made vivid pathways of discovering and sharing better questions and treatments. And third, I wanted to help amplify the amazing work this communities of non-academics was doing so more people and communities could develop their own pathways.

I was sitting next to Eric Hekler during the talk and shared with him that this is the exact type of community our research talents could help. Over the next while (a year or more) I fell into the role of supportive ally while Eric and Dana pulled together the RWJF proposal to support Dana as PI in the first of its kind grant with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. I enjoyed the novelty of the grant, being involved, and I tried to help out when invited.

Over the course of the grant I have cherished our monthly meetings, the conversations between kind, curious, talented people have been fascinating and eye opening. I looked forward to the handful of times that the PI’s from Seattle, San Diego, Boston, and Tempe were able to get together and have a day advancing the work and listening respectfully to each other. And the event, led by Dana and John, put on in DC, May 3rd, that brought together similar health communities has been transformative in how I see the relationship between academics and communities, especially health communities. It was in listening humbly at this event (and seeing some elite academics fail to)… where the origins of the humility audit for authentic and meaningful collaboration became core to my thinking of research in service of communities.

I do have two regrets. One I have known about all along, the other I was surprised to discover.

The regret I have known from the beginning is that I could not be an equal partner in this project because I could not spend the amount of time or energy that I believe this work deserves. This is in part a structural limitation. The funding for the grant is a primary source of income for Dana and the topic and the research are part of her identity and daily work. Conversely, funding wise, my part from the grant was about 1% of my income over the period of the grant. And while it was the first among dozens of projects, it still had to compete with the accountabilities I had on those other projects and the responsibilities that come with teaching, launching a new research center, and running a Ph.D. program. Although I put in probably 10 times the effort the budget suggested I should and I tried to always be present in conversations, meetings or workshops, I never felt I was doing enough. Knowing that an opportunity to work with this team and this community is so rare, I regret that my other responsibilities kept me from participating more fully.

The regret I just recently learned is in realizing that although my institution allowed this new type of grant (with Dana as PI) to be processed, that is very very different than prioritizing the work and supporting her as she deserves. At our final meeting of the grant as we were discussing other communities that could benefit from collaborating with academics, Dana wrote on the board, “It feels like a trap”. For some background, when Eric left ASU for San Diego, I took over as the main point-of contact at ASU. The combination of a new type of grant, multiple schools involved, both Eric and myself changing schools and/or universities mid grant, and a reduced role from our main administrative assistant led to an unusually high level of miscommunication, delays, and frustration in the execution of basic functions of the grant. At the same time ASU and RWJF were so excited about a new model of research that RWJF supported a second such grant to a different research team and DIY health community. What I did not realize was although we were able to process these grants, the ASU research infrastructure was not designed to prioritize, support, or even know the unique needs of patient researchers. I am learning the difference between the design of an institution that allows a behavior and one that supports a behavior. Because of what I have learned from this second regret, I will continue to work to change models of social embeddedness, community support, and academics from within by both doing and advocating.

I am unsure exactly what the end result of being involved in this work will be. I reference it regularly to guide more inclusive and supportive research models in other contexts. It has transformed my thinking by revealing unanticipated blind spots. I have also learned so much from Dana and the rest of our team. What I know with certainty is that I am grateful to Dana for making space for me on this pathway!

Eric Hekler’s partner narrative

“Saving Mr. Scientist”

For me, this began with seeing Dana give an incredible talk at the QSPH conference. I was really moved and thought that what she and the OpenAPS community were doing was fascinating, powerful, and important and I wanted to help. I went up afterward, first talking with Scott, to offer help and discussed the idea with also Brian Sivak and Steve Downs from RWJF; the goal was to explore possible ways of helping the group find funds and support. At first, my intuitions were that, because I was a “scientist,” one thing I could offer would be to do an “objective evaluation” of OpenAPS. If the evaluation worked out, it would help provide “validity” to the work Dana, Scott, et al were doing. When Dana and I first starting talking, that was the initial offer I provided with good intention.

My first hint that that might not have been right came when I spoke to Dana about this “offer” of “help.” In brief, she didn’t buy it and, while she was very kind as we didn’t know one another very well at that point, definitely was sending out cues that the “offer” was not what she wanted or needed. Based on that, I pivoted and asked something to the effect of, “how can I help?” This was the key starting point for me in my transition towards wanting to be not merely a researcher but also a partner to those I seek to support in my professional career. The first step was realizing that the most important thing I needed to do was to take the time to try and listen, observe, and understand as best as I could, rather than jump in with my thoughts, my interests, my agenda, etc.

As Dana and I and the team have been working together, I have had many many more changes of thinking, understanding, and learning, that has drastically impacted my understanding of what I see as my role as a “professional,” “scientist,” “educator,” or “professor,”; all labels and identities that are part of how I see myself. (and, in case you didn’t pick it up yet, every time I put something in quotes, it’s a story in my head; Often an identity for me or a resource I felt I could provide that ended up not being right and, likely, leading to unintended consequences).

The next important set of interactions were Dana and my many conversations while we were developing the grant. During these times, my initial intuitions were to be the “PI” because that’s what I was “supposed” to do. I was excited about the ideas and so I wrote out lengthy drafts of what the grant could be about and then “offered” them to Dana to review and edit. My thought was that, while we were discussing things together, my role was to “synthesize” and “translate” this work into something that RWJF would care about. During phone calls, initially, I felt the need to play the role of a “moderator” to “help” create “bridges” between Dana and the professionals we met with.

Thankfully, both Dana and Paul Tarini, with wisdom and tact, helped me to understand a false story I was engaging in. In brief, we realized that this project was not my science but, instead, it was Dana’s. This meant that it made no sense that I was trying to lead. Dana, Paul, and I had a discussion about this and we decided to basically restart the process for all involved with a very clear focus that Dana is leading this; Dana is the PI. I distinctly remember the first phone conversation when we did this. The conversation started with me mansplaining what we already knew and agreed upon; thankfully, Paul, again, had the great wisdom to say to me effectively, “Eric. Stop. Dana, what do you want to talk about.” Even though I rationally understood what we were doing and why I didn’t get it emotionally and I fell into bad habits and traps.

My education only continued.

One of our key activities was to organize a convening to understand and build a space for differences in perspectives towards opening pathways for innovation. Some key insights and thoughts on this convening have already been written about quite a bit amongst our blogs. I wrote up my experience in a blog called bearing witness. To summarize, when doing the planning for the convening I, again, fell into the trap of thinking that my role in this was to be a “synthesizer” and to help “drive” the discussion. Instead, Dana and John assigned me the role of a notetaker. As I write in that blog post, this was a profoundly important role for me to take, personally and also for the meeting to achieve one key goal, which was equitable participation and contribution. In brief, if I had played my traditional role I would have, very likely, crowded out others’ thoughts. I needed to learn that, sometimes (perhaps often) the best thing I can do is sit, listen, and seek understanding, or what I called bear witness. In essence, that meeting gave me some emotional/experiential understanding of what it means to bear witness and the foundational importance of doing so, particularly as someone with strong relative and entrenched powers afforded to me by our culture.

After this meeting, Dana and I discussed this experience with Paul, Erik, and the team. Paul suggested we talk with others who have done work on issues of power and power differentials in society. We started to connect more with those individuals who work with people who experience marginalization and to work towards learning languages and ways of thinking that could help us to organize and understand our thinking. From this, I started to really hear of the powerful and important role of stories and storytelling, particularly being aware of my own stories.

As a behavioral scientist, I NEVER thought it was my role to discuss or understand my own subjective experience and, most definitely, I never thought it was appropriate nor even valuable for me to tell my stories and experiences as part of my professional career. Of course, that’s not exactly true as, whenever I give talks, I embed small stories. That said, I always thought that the stories were there just as a form of communication to make the “real ideas,” the “real wisdom” and the “real work” of science more easily understood by those who “don’t really understand science.” Prior to this project, stories were just a cheap and easy way to convey the “truly important” information that science offers. If stories were offered alone, they would be mere anecdote and, thus, should be brushed aside as secondary and unimportant until the “real science” can happen to generate “real insights.” As I hope you are picking up from me writing out my story right now, I don’t believe that personal stories should be relegated to the “anecdote” bucket but, instead, should be understood and valued for themselves. The key lesson in my journey was to learn how to know myself well enough so that I know when I may be bringing bias and problems into my work. Prior to this project, I had understood issues of bias rationally; now I’m starting to see how examining one’s story can actually help a person know when they are bringing themselves into a process vs. not.

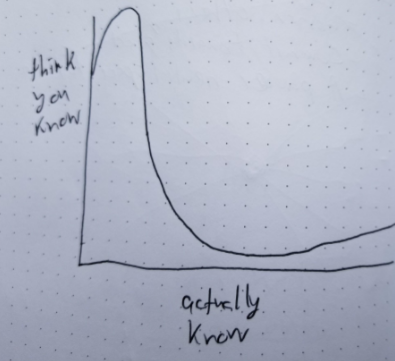

I continue to learn more each and every day and feel so very grateful for it. To give you a sense of the most immediate lesson I experienced, you need to know a bit about the Dunning-Kruger Effect. The basic idea is that there are people who have high confidence and, simultaneously,low competence or, put slightly differently, high ignorance of a topic and, likely because they are ignorant, they don’t realize how much they don’t know about a topic, thus rating themselves higher on confidence in their knowledge of a topic. This idea, at least in my circles, is popping up all over the place, such as trying to understand Donald Trump, Elizabeth Holmes as a concrete example of the perils of the “fake it til you make” culture of Silicon Valley; as a plausible explanation for Silicon Valley and beyond such as the failed Fyre Festival, and even coming up around the possibility that people of higher social economic status may have inflated confidence compared to competence. This concept is scaring the $^*& out of me as it suggests that people who are ignorant are confidently ignorant, thus not allowing feedback to get in.

So… how does this connect with my story of being a partner for Dana and her work? At some point, Dana drew a simple little diagram for me during one of our discussions when I was particularly down on myself and not trusting my intuitions. Here’s a basic recreation of it:

She told me, without any judgment, that, when she and I first met, I was at the top of the upper left side of that diagram; I thought I knew a lot but, point-of-fact, I didn’t know all that much about the work we were going to do together. As we’ve worked together, according to Dana, I’ve moved along the X-axis. When Dana first brought this up to me, she was sharing with me her experience of me as someone that is learning and getting beyond high confidence, low knowledge.

This came up again during our last in-person meeting together as Dana, almost as an aside, said that I had fallen into the Dunning-Kruger Effect issue early on in our working together but that I’ve moved beyond it, at least in our current context. This might seem strange, but I had not personally made the linkage between the Dunning-Kruger Effect, the diagram Dana drew, and my lived experience. Prior to that, I held the belief that I was someone that would “know” when I was falling prey to this big problem. Obviously, though, that’s not the case. After some more reflection about this, I think Dana was right about me; through compassionate honesty and, I think, a strong relationship built on balanced power, mutual respect and trust, she helped me to make progress and get beyond my own experience of high confidence/low competence.

This last point has been the most profound for me to learn to date. As a white male who did my postdoctoral training at Stanford/Silicon Valley, my context and the signals I received from our culture set me up to be confidently ignorant. I’ve been told all my life that I’m, de facto, a “good person” who, through “my objective professionalism,” could offer “solutions” and “help” others. Now I’m not so sure, and I am so very thankful for my humility.

To be sure, this doesn’t mean I don’t want to keep trying to do what I can to be a good person; it just means that my understanding of power, professionalism, and objectivity, have all expanded far beyond what I had realized was possible prior to this work. I now have some emotional signals that can help me to feel when I may be falling into traps. I’m also now aware of the need to be mindful of things I may be blind to when starting a relationship with anyone. Rather than fall into the trap of trying to be objective, I realize now that each person’s subjective experience, or perhaps said more simply, recognizing that each person is human, is an important part of the process. When one person is “stronger,” “better,” “smarter,” or “more powerful” in some way, then the feedback loops that could feasibly reduce these inequities don’t occur. This results in confidently ignorant people with good intentions (i.e., people like me) doing more harm than good and having no clue that it’s happening.

I look forward to continuing this journey and am so very grateful for the time Dana has honored to give me. Like how I thought Mary Poppins was about Mary Poppins, I always thought this project was about Dana and helping patient innovators. While that remains true, again, just like how Mary Poppins was also a lot more about Saving Mr. Banks, I realize now that this project was also an opportunity to save Mr. Scientist (i.e., me) from my professional, objective, confident ignorance.

John Harlow’s partner narrative

I met Dana Lewis after being dumbfounded by the theatricality, style, and substance of her 2016 Quantified Self Public Health conference presentation. After that showstopper, a member of my dissertation committee (Eric Hekler, still a collaborator on this very project) sought her out to try and build a partnership. Luckily, because Eric is exceptionally flexible and open to the perspectives and goals of others, he was able to pivot towards Dana’s interests, and invited her to give a talk at Arizona State University (ASU), where Eric and I worked. This emerging collaboration eventually evolved into the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) grant: Learning to Not Wait: Opening Pathways for Discovery, Research, and Innovation in Health (and Healthcare). This grant was made to Dana Lewis as the patient-Principal Investigator (PI), breaking new ground for ASU and RWJF alike. I explored some of the team culture we built leading up to applying for the grant on the Opening Pathways blog, and I’d like to share some further thoughts here about how and why our team found success.

From this project, I have learned that the barriers to entry for academics and institutional partners working with patients are “soft” skills, rather than the “hard” skills or technical scientific skills. The skills I have used most working with Dana are empathy, building trust, listening, and translation. The key to partnerships like these is empathizing with people whose experiences are not like one’s own, so I practiced active listening, radical openness, and refraining from using my own experience as a baseline. Building trust this way also requires translation by understanding how context differs, and building communication least likely to be misunderstood (different than most accurate!), and most likely to make sense and be accessible to its intended audience.

For example, I am less authoritative with Dana than with other partners. I have found that if people are taking on something new or outside their expertise or experience, they often gravitate to confidence. That has led me to be authoritative with partners, and to act as though I perceive myself to be an expert. I have benefitted from being confident and authoritative about my ideas, and having them open opportunities for me. (I do acknowledge the role of white, middle-class, cis-male privilege in this.) However, in working with Dana, I have reflected on the political economy of a patient-PI from outside the academy, and done my best to grant and respect her authority in our work. I have focused on listening and executing, rather than stating and defending my ideas, because I want to communicate and model that the PI power and decision-making lies with Dana.

What has surprised me most about this partnership is how deep the differences are between the academy and Dana’s baseline, and how I have learned over time what makes Dana’s experience so different. Another surprise was the appetite, intensity, and gratitude I felt at the Opening Pathways Convening. Most meetings are within a certain range of experience, but this was different, and it revealed how connectivity in this space could be a platform for future innovation.

I’ll close with this advice if you are considering taking on a project in collaboration with a patient: Listen. Give them your power. Support their vision.